Even though U.S. consumers routinely buy and eat genetically engineered corn and soy in processed foods — most are unaware of the fact because the GE ingredients are not labeled.

When consumers are asked in surveys whether they would buy genetically engineered (GE) produce such as fruit, most say they would not buy GE produce unless there were a direct benefit to them, such as greater nutritional value.

Yet with continuing invasions and spread of exotic insects and diseases for which there is no known control, the potential importance of trees or vines with some form of genetically engineered resistance is on the rise. In California, such diseases include Pierce's disease in grapes, crown gall disease in walnuts, and the invasive citrus greening (huanglongbing or HLB) in citrus.

"These are potentially devastating diseases to California growers, who produce 70 percent of the fresh fruit and nuts for the entire United States," notes Victor Haroldsen, scientific analyst at Morrison and Foerster, in the current California Agriculture. "They are also a mainstay of the California economy. Fruit and nut tree crops accounted for one-third of the state's total cash farm receipts, or $13.2 billion in 2010."

Now, however, Haroldsen reports that there may be a way to satisfy both consumers and growers — called "transgrafting."

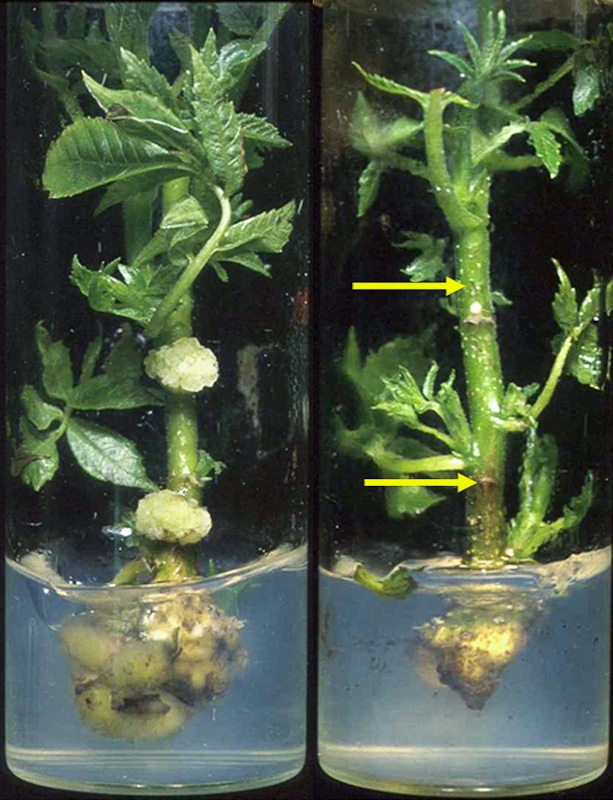

"In transgrafting the genetically engineered rootstock can potentially confer the whole plant with resistance to disease. Yet the rootstock does not transfer the modified genes to the fruits or nuts produced," said Haroldsen.

Although over 10 years old, transgrafting technology is just now nearing commercialization, partly due to the long generation times of most trees and vines. Two such transgrafting applications are: a crown gall-resistant walnut rootstock, and a grape rootstock that confers moderate resistance to Pierce's disease.

"The key advantage of transgrafting is that the plant's vascular system can selectively transport across graft junctions the proteins, hormones, metabolites and vitamins from the roots without changing the heritable genes or DNA sequence in the fruit or nut." says Haroldsen.

In recent research at UC Davis, Haroldsen (a former graduate student) and his colleagues confirmed that modified DNA and full-length RNA from the rootstock does not cross the "graft union" into the scion, in the walnut and grape applications, or in a tomato model of these two systems.

"These current GE applications address root or xylem pests and diseases, but future applications will likely target traits aimed at consumer needs such as increased nutritional value or improved flavor," said Haroldsen. "If perceived risks to personal health and the environment could be reduced, genetic engineering could benefit not only growers but Californians around the state," he adds.